May 5th is traditionally called “Tango no Sekku,” also known as Children’s Day in Japan, a day to pray for the healthy growth of boys.

My cooking school gets decked out with carp streamers every year, using ones given by my grandfather.

Tango no Sekku is a seasonal event with a long history. Originally, it was not only about boys but about warding off evil spirits and wishing for the family’s well-being.

This time, let’s take a journey back in time to explore the origins and food culture of this special occasion.

From the Heian Period

Tango no Sekku, one of the five seasonal festivals, is a tradition that came from ancient China. The word “tan” means “beginning,” and “go” means “five.” So the day when the two fives line up—May 5th—became known as “tango.”

In the famous Heian period work ”Makura-no-Soshi” (The Pillow Book), it says:

“There is no month like the fifth month. The fragrant mingling of iris and mugwort is delightful. From the Imperial Palace to the homes of the common people, houses are decorated thickly with them. It is truly rare and charming.”

From these writings, we can tell that the festivities on May 5th were grand even during the Heian period.

Shobu and Martial Spirit

During the Heian period, people adorned their homes with “kusudama” on Tango no Sekku. Kusudama were balls filled with fragrant herbs like iris and mugwort, and most of them had artsy five-colored threads and were hung from columns. The iris and mugwort custom was from China, to ward off evil spirits and keep bad luck from entering the home.

Today, we can still see fancy kusudama, a bit different from the original though, like big, round confetti poppers used for celebrations like new store openings.

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573) or the Sengoku period (1467–1600), military clashes raged on among local warlords, or “daimyō,” who fought for power and land after the central shogunate went downhill.

That’s when the pronunciation of “shobu (菖蒲),” or iris, the flower of the season, got associated with the same sound of “shobu (尚武, martial spirit)” or “shobu (勝負, contest).” This connection started the festival to pray for boys’ strength and success, shaping the celebration we know today.

In the Edo period, markets in Nihonbashi sold imitation armor and swords, and people of all classes would eagerly buy them to decorate their homes. To this day, many families with boys enjoy displaying a fancy Japanese warrior helmet and armor at home on Tango no Sekku.

Food Traditions of Tango no Sekku

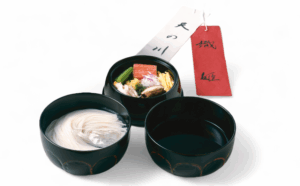

The dishes served during Tango no Sekku often have a festive feel to them, reflecting the martial spirit. You’ll find a lot of symbolism in them, including carp dishes, inspired by the Chinese legend of a carp climbing a waterfall to turn into a dragon, and “gusoku-ni” which is simmered spiny lobster (or “ise-ebi”) looking like an armor, and “kabuto-ni” with a head of simmered sea bream.

For gifts, popular picks are “kashiwa-mochi” (oak leaf-wrapped rice cakes) and “chimaki” (rice dumplings wrapped in leaves).

Kashiwa-mochi caught on around the mid-Edo period, especially in the Kanto region. The kashiwa (oak) leaf, once used in steaming rice, symbolizes prosperity because the old leaves hold on to the trees until new leaves grow.

Traditionally, Kyoto and other western regions opted for chimaki instead of kashiwa-mochi. You’ll find “hoko-chimaki,” the Kyoto version, looking sort of like the sacred pikes used to ward off evil spirits. Over in Shikoku and parts of Kyushu, rice cakes are wrapped in round and thorny “sankirai” (smilax) leaves, symbolizing longevity and protection.

Chimaki means “wrapped in chigaya grass,” though you see bamboo leaves used more often these days. Chimaki comes in a variety of shapes, like the conical “hoko-chimaki,” the flat triangular “Echigo-chimaki,” and even a Chinese-style chimaki with tasty fillings. Some others make “aku-chimaki” by soaking glutinous rice in lye or natural soda before steaming it.

Tango no Sekku is a day filled with the prayers and hopes of people for generations. Whether you have carp streamers, iris leaves, kashiwa-mochi, or chimaki, they help keep the day’s traditions alive, continuing our cultural heritage into the future.