Hinamatsuri, or the Doll Festival, is one of Japan’s cherished spring traditions.

As the peach flowers start to bloom, homes are filled with nicely decked-out Hina dolls, colorful rice cakes, and crispy hina-arare, creating a festive vibe where families wish for their daughters’ healthy growth and happiness.

This celebration has a long, rich history, with interesting meanings behind each custom and dish. In this article, we’ll explore the origins of Hinamatsuri, the correct way to display Hina dolls, and the traditional foods that make this festival special.

What is Hinamatsuri?

In the past, it was a festival held around the beginning of March, known as “Joumi-no-Sekku” (the Festival of the First Snake Day), so it’s sometimes called that. Along with other seasonal festivals like the “Tango-no-Sekku” on May 5th, the “Tanabata” on July 7th, and the “Chouyou-no-Sekku” on September 9th, it has been celebrated since the Heian period as one of the Five Seasonal Festivals.

In the old lunar calendar, it roughly coincides with the peach blossom season, so it’s also known as the “Peach Festival.” In ancient China, peach trees have long been considered to have the power to ward off evil, and in Japan, peach blossoms have been loved for ages, even appearing in poems in the “Man’yōshū”. In fact, peaches have medicinal properties and are said to be good for things like heat rashes.

Speaking of peach-themed exorcisms, I remember when I was a kid, the “Kuonshi” (Chinese hopping vampire) movies were really popular. In those films, people would fight off the Kuonshi with swords made of peach wood. I guess it’s that same peach magic at work!

The Origins of Joumi-no-Sekku

Originally, in China, people used to purify themselves by cleansing at rivers on the Joumi day, and this custom spread to Japan, where it began to be observed around the Nara period. By the Heian period, the imperial court held a “Kyokusui-no-En” (a poetry contest over a winding stream) on this day. The “kyokusui” was a winding waterway created in the garden, and participants would float cups of sake on it and compose poems before the cup passed them by. It was a very elegant activity.

In Japan, people would traditionally write their misfortunes onto paper dolls, known as ”yorishiro” (a kind of spirit medium), and float them down the river as a way to rid themselves of bad luck. During the Muromachi period, this custom evolved into the practice of decorating “hina dolls”; a pair of dolls representing the Emperor and Empress, and by the Edo period, it became widely popular among people, with more luxurious clothing and decorations for the dolls. Some areas, like Tottori, still practice nagashi-bina (floating hina dolls) to this day.

How to Display Hina Dolls

The way hina dolls are displayed actually varies depending on the region. In Tokyo, typically, the male doll (the “odaishisama”) is placed on the left, and the female doll (the “ohinasama”) on the right, but in Kyoto, it’s the opposite.

Originally, the Kyoto way of arranging the dolls was considered the proper method. However, after the Meiji Restoration, Japan started adopting Western customs, and even the positions of the Emperor and Empress changed to the Western style.

In the Heian period, the left minister had a higher rank than the right minister, and the left side was considered more prestigious because, when facing south (which was the Emperor’s direction), the left side would be facing east, the direction of the rising sun. So, it was customary to place the man on the left and the woman on the right.

The Meiji Restoration was a time when Japan drastically changed its ways. I imagine it might have felt strange to change the positions of the hina dolls, but it probably reflects the boldness of the Japanese people, who were willing to mix new things with old traditions and rapidly make big changes when needed.

Foods and Sweets for Joumi-no-Sekku

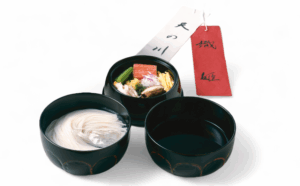

On Joumi-no-Sekku, people eat “chirashi-zushi” (scattered sushi) and “hamaguri” clam soup. Around this time, the water temperature starts to rise, and shellfish like clams become delicious. Since clams are a symbol of marital harmony (because they have matching halves), they’re often used in this dish. For sweets, there are colorful “hishimochi” (diamond-shaped rice cakes) and “hina-arare” (sweet rice crackers).

The custom of using “hishimochi” for Hinamatsuri began during the Edo period, and the red, white, and green stacked rice cakes, cut into diamond shapes, became a beautiful addition to the hina doll displays.

“Hina-arare” is an easy-to-make sweet at home. Traditionally, “arare” is made from rice, but at home, it’s easier to use mochi (sticky rice). To make them, you cut the mochi into small pieces, let them dry on a sieve for 2-3 days until they crack, and then fry them quickly in oil at around 170°C. Once fried, you color them with green matcha, white soybean flour, and red strawberry powder (dried fruit powder).

Originally, “hina-arare” was made from popped rice, which, when it bursts, makes a sound like a bell, symbolizing protection from evil spirits, similar to how bells are used as charms. For example, during the “Omizu-tori” (water-fetching) ceremony at Todai-ji Temple, the monks walk around the sanctuary chanting prayers while scattering roasted rice as a way to ward off evil spirits.

Chirashizushi is a type of decorated sushi bowl where ingredients like shiitake mushrooms, abura-age (fried tofu), carots, thinly fried eggs, silk pods are added to sushi-meshi (vinegered rice). Those colors of ingredients stand for four seasons and also add beautiful color to the festival.

Hinamatsuri is a vibrant festival, and since this season is full of different delicious dishes, trying them out can make your Hinamatsuri celebration a lot of fun!